Heute wende ich mich an Sie, liebe Nobelweintrinker, die ihr ständig vom Burgund schwärmt und die funkelnden Roten der Côte d’Or für die besten Weine der Welt haltet. Euch, die ihr so gern in der Opulenz eines Bonnes-Mares badet und ehrfürchtig vor der Kraft und Feinheit eines Chambertins verbeugt – euch möchte ich heute einen anderen burgundischen Wein ans Herz legen… den Beaujolais.

Buht mich ruhig aus, faucht mich an, schmeißt Tomaten nach mir, wenn ihr mögt: Ich werde mit Stolz das scharlachrote „B“ tragen, dass hernach meine Brust schmückt. Ich bin ein unerschrockener Getreuer dieser Bewegung und werde es immer sein, egal wie tragisch sich dieser Bund auch gestalten mag.

Beaujolais – kein unflätiges Wort

Gewiss verstehe ich, dass die meisten Leute es weniger beleidigend gefunden hätten, wenn ich diesen Text mit einem Kraftausdruck begonnen hätte. Oder Sie hätten vielleicht etwas die Stirn gerunzelt, wenn ich den Namen des Herrn geradewegs beleidigt hätte.

Gewiss verstehe ich, dass die meisten Leute es weniger beleidigend gefunden hätten, wenn ich diesen Text mit einem Kraftausdruck begonnen hätte. Oder Sie hätten vielleicht etwas die Stirn gerunzelt, wenn ich den Namen des Herrn geradewegs beleidigt hätte.

Beaujolais ist kein „unflätiges Wort“, wie viele meinen. Noch vor 100 Jahren erzielten die besten Weine aus Morgon deutlich höhere Preise als die heute fürstlich bezahlten Premier-Crû-Weine aus Gevrey-Chambertin. Wie weit haben wir uns von unseren Wurzeln entfernt?

Behaltet im Gedächtnis, dass vor dem berühmten Dekret des Herzogs von Burgund gegen den Anbau der Gamay im Jahre 1395 diese Rebsorte als genauso edel erachtet wurde wie die Pinot Noir und in vielen der vornehmsten Lagen der Côte d’Or gedeihte – auch wenn diese Tatsache heute seltsam klingen mag.

Bessere Traubenreife aufgrund der südlichen Lage

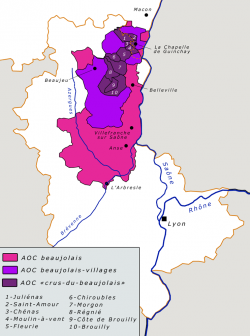

Betrachtet man die Faktoren, die einen großen Wein außerordentlich machen: Im Hinblick auf den Boden weisen die besten Lagen verschiedene Mischungen aus Ton, Sand, vulkanischer Lehmerde und sogar Kalkstein auf. Aus jeder der zehn kommunalen Appellationen, die das Beaujolais besitzt, kommt ein ganz eigener Gamay-Stil. Aufgrund der im Vergleich zur Côte d’Or südlicheren Lage und des damit verbundenen Klimas reifen die Trauben im Beaujolais früher, wodurch sich eine gleichbleibend hohe Qualität von Lese zu Lese unterstellen lässt.

Ungewohnt für unseren Gaumen

Ein stichhaltiges Argument hat Eric Asimov 2009 in einer seiner wöchentlich erscheinenden Kolumne in der New York Times vorgebracht: „Es ist das Marketing, das das Image des Beaujolais kaputt gemacht hat, indem es ganz auf Beaujolais Nouveau gesetzt und den leichten, charmanten Bistro-Wein, der der Beaujolais war, vergessen hat. Die Vermarktung des Beaujolais als Nouveau hatte eine rein lokale Tradition aufgegriffen und diese dann weltweit vermarktet. Trauriges Resultat: kommerziell hocherfolgreiche Weine, aber qualitativ banal – tutti-frutti-Weine.“

Ein stichhaltiges Argument hat Eric Asimov 2009 in einer seiner wöchentlich erscheinenden Kolumne in der New York Times vorgebracht: „Es ist das Marketing, das das Image des Beaujolais kaputt gemacht hat, indem es ganz auf Beaujolais Nouveau gesetzt und den leichten, charmanten Bistro-Wein, der der Beaujolais war, vergessen hat. Die Vermarktung des Beaujolais als Nouveau hatte eine rein lokale Tradition aufgegriffen und diese dann weltweit vermarktet. Trauriges Resultat: kommerziell hocherfolgreiche Weine, aber qualitativ banal – tutti-frutti-Weine.“

Doch es gibt Hoffnung. Asimov hat nämlich festgestellt, dass die Öffentlichkeit den Marketingtrick durchschaut hat: „Der Beaujolais Nouveau-Rummel erzeugt nur noch Langeweile, in den Vereinigten Staaten wird die Arrivage des Beaujolais Nouveau nur noch mit Gähnen quittiert.“

Vom Nahrungs- zum Genussmittel

Nicht nur in den USA, auch in Europa. Und die Beaujolais-Produzenten spüren es. „Bekanntlich sind die Produzenten des vin ordinaire, also einfacher Landweine, heute in Schwierigkeiten – in Bordeaux, im Languedoc und auch im Beaujolais”, so Asimov.

Der Satz erinnert mich an ein Gespräch, das ich im Sommer 2006 mit dem berühmten Weinmacher Jacques-Frédéric Mugnier in Chambolle-Musigny im Burgund führte. In diesem Gespräch zeigte er auf, wie sich die Prioritäten unter den Weinmachern geändert haben – speziell in Frankreich. „Als ich ein kleiner Junge war, tranken die Leute in meinem Dorf nicht Wasser zur Erfrischung, sondern einen gut gekühlten, leichten Wein oder ein Bier“, erzählte Mugnier. „Diese Zeiten sind vorbei. Wein ist mittlerweile ein Genussmittel, kein Nahrungsmittel mehr…“

Der Satz erinnert mich an ein Gespräch, das ich im Sommer 2006 mit dem berühmten Weinmacher Jacques-Frédéric Mugnier in Chambolle-Musigny im Burgund führte. In diesem Gespräch zeigte er auf, wie sich die Prioritäten unter den Weinmachern geändert haben – speziell in Frankreich. „Als ich ein kleiner Junge war, tranken die Leute in meinem Dorf nicht Wasser zur Erfrischung, sondern einen gut gekühlten, leichten Wein oder ein Bier“, erzählte Mugnier. „Diese Zeiten sind vorbei. Wein ist mittlerweile ein Genussmittel, kein Nahrungsmittel mehr…“

Vielleicht wird der Beaujolais eine Renaissance erleben. Vielleicht wird es möglich, ihn wieder zu genießen. Vielleicht wird er wieder in die Bistros zurückkehren – in jene Bistros, die heute noch belanglose, industriell hergestellte Weine anbieten. Es wäre an der Zeit, die wahre Identität der Beaujolais-Weine wiederzuentdecken.

In der nächsten Folge werde ich Ihnen ein paar Empfehlungen geben – sowohl für den Keller als auch für den täglichen Konsum.

The Robinhood Chronicles (1):

The Bandit of Bayernshire Robs Beaujolais Blind; Returning with riches fit for a king, at prices even a Friar can afford. By Justin G. Leone

Robbing from the rich, and giving to the poor seems like an oddly justifiable, almost admirably charitable, crime. After all, any kingdom referred to as the “Slope of Gold,” can surely spare a few alms for the poor. This, unfortunately, is pure fantasy. Our benevolent sovereign, her majesty and royal highness, the Cote d’Or, is dreadfully quick to call in any and all debts owed to the treasury of discernibly fine taste. So, for my fellow countrymen whose palates lay sorrowfully fallow; bathed not in the opulence of Bonnes Mares, nary anointed by the awesome virility of Chambertin, I offer thee a compress for thine wounds, the salve for thine burns; I present thee, Beaujolais.

That’s right, Beaujolais.

Boo, hiss, throw tomatoes if you like, I shall proudly bear any scarlet “B” emblazoned upon my breast hereafter. I am an unabashed loyalist to this movement, and shall always be, regardless of how apparently tragic the association has become. I do understand, of course, that most people would find it less offensive to simply begin the article with a four-letter word, or perhaps raise a few eyebrows by taking the Lord’s name in vain straightaway. Better yet, to accuse your dear mother of having a less than adequate grip on parenting. But Beaujolais? For heaven’s sake, where does he get the nerve?

The truth is, I consider myself to be fortunately enlightened. Beaujolais is not the “dirty” word it is so often accused of being, but rather, a quite necessary part of our everyday wine vernacular. Or, at least, it should be. To think, that just one hundred years ago, the best examples of Morgon fetched far higher prices than the now princely premier crus of Gevrey-Chambertin. How far we have come from our simpler, yet perhaps more sensible, roots.

Bear in mind, that prior to the Duke of Burgundy’s decree against the planting of Gamay in 1395, these vines were considered just as noble as Pinot, and comprised much of the most lofty properties in the Cote d’Or. Though this might ring a might dissonant in our modern ears, consider the factors which make a great wine so extraordinary; as soil is concerned, the best sites have various mixtures of clay, sand, volcanic loam, and even limestone, which, in the case of Beaujolais, lie atop the most prehistoric of all geologies in the very same prehistoric bedrock-granites which constitute the Earth’s crust. From each of the 10 “Crus,” or named Villages, comes a distinctly unique style of Gamay, much as Pinot in the Cote is known, more for its provenance than its variety. In regards to climate, being more southerly than the Cote itself, ripeness is often slightly easier to achieve, thus assuming a higher consistency of quality from vintage to vintage.

Why, then, is Beaujolais so unfamiliar to our modern palates?

One solid argument is proposed by Eric Asimov, in a 2009 publication of his weekly New York Times column: “Marketing, of course, is what transformed the image of Beaujolais from a light and Charming bistro wine to Beaujolais Nouveau. The annual roll-out-the-barrels of Beaujolais Nouveau took a quaint local harvest celebration and made it a worldwide phenomenon, sadly centered on wines that were largely tutti-frutti and banal.”

However, there is hope, as he notes the new public conscious becomes wise to such schemes, “Novelty begat boredom, and in the United States, at least, the annual arrival of Beaujolais Nouveau has been met with yawns for some time now.”

I can personally remember, back home in Chicago, the ridiculous pomp and circumstance surrounding George Debeouf’s annual Nouveau release, complete with garishly flowered bottles of insipid, vinified dispassion far as the eye could see. This was a pivotal time in America’s developmental drinking history, with the advent of Robert Parker’s choke-hold upon the popular palate, and the rise of several influential publications, wine bars, star-sommeliers, television series, etc, all simultaneously shaping the popular palate. Americans, who would soon constitute the largest export market in the world for many European producers, one could assume to have christened their soon-to-be-astutely-stocked cellars with a bottle of basic Beaujolais Nuveau. Even I vividly remember guzzling the stuff until I couldn’t stand; Then again, I was twenty-two. Of course, living through the wretched morning thereafter was hardly worth the cover charge, regardless of how meager it may have been. In my mind, as the culprit could still be considered “wine” of some basic sort, I could at least claim the indulgence to rate slightly higher, culturally speaking, than drowning in a pool of aspartame-riddled energy drink spiked with cut-rate vodka. A fine, yet important, distinction. But enough about me…..I digress.

Asimov continues by commenting on the current state of the international wine market, adding “As has been well documented, producers of vin ordinaire, whether it comes from Bordeaux, Languedoc, or Beaujolais, have been in trouble for some time now.” This reminds me of a rather seminal interview I once shot with famed winemaker Jaques Frederic Mugnier, of Chambolle-Musigny, Burgundy, in summer of 2006. In the interview, he offers a rather insightful view of how priorities have changed amongst winemakers, especially in France; “As a boy I can still remember, even in my generation, in my small village in Burgundy, a time when people didn’t drink water for refreshment. Instead, they drank a well chilled light wine, or beer.” Long gone is this generation of drinkers; opting for anything vinified, fermented, or brewed over water, still weary of tainted sources and possibility of disease. Skepticism has been replaced by sensationalism; wine becoming more fashion than sustenance, and the sale of an otherwise necessary element of daily life, now becoming ruthless corporate business. When once upon a time, Beaujolais could be found in every home wine rack, and in every bistro, slugged back by the carafe-full, there are now bottes of industrial-grade Australian gaff hiding behind labels unashamedly brandishing furry woodland creatures and flaunting pseudo-risquee cuvee names. It’s time to re-discover the true identity of Beaujolais, and re-introduce these wines as the legitimate, complex, beautiful wines that they are. Let’s begin with the basics, and progress to a few recommendations to seek out, both for your home cellar, and daily dinner table.

Hallo Justin,

zum Thema “gut gekühlter, leichter Wein zur Erfrischung” (Jacques-Frédéric Mugnier) siehe auch unseren dreizehn°-Blog “Kalter Rotwein für heiße Tage: Frevel oder Freiheit?” unter http://blog.13grad.com/2012/08/kalter-rotwein-fur-heise-tage-frevel-oder-freiheit/.

Vielen Dank auch nochmal für deinen sehr anschaulichen Vortrag beim Genussfestival über Fisch & Wein.

Gruß

Jan